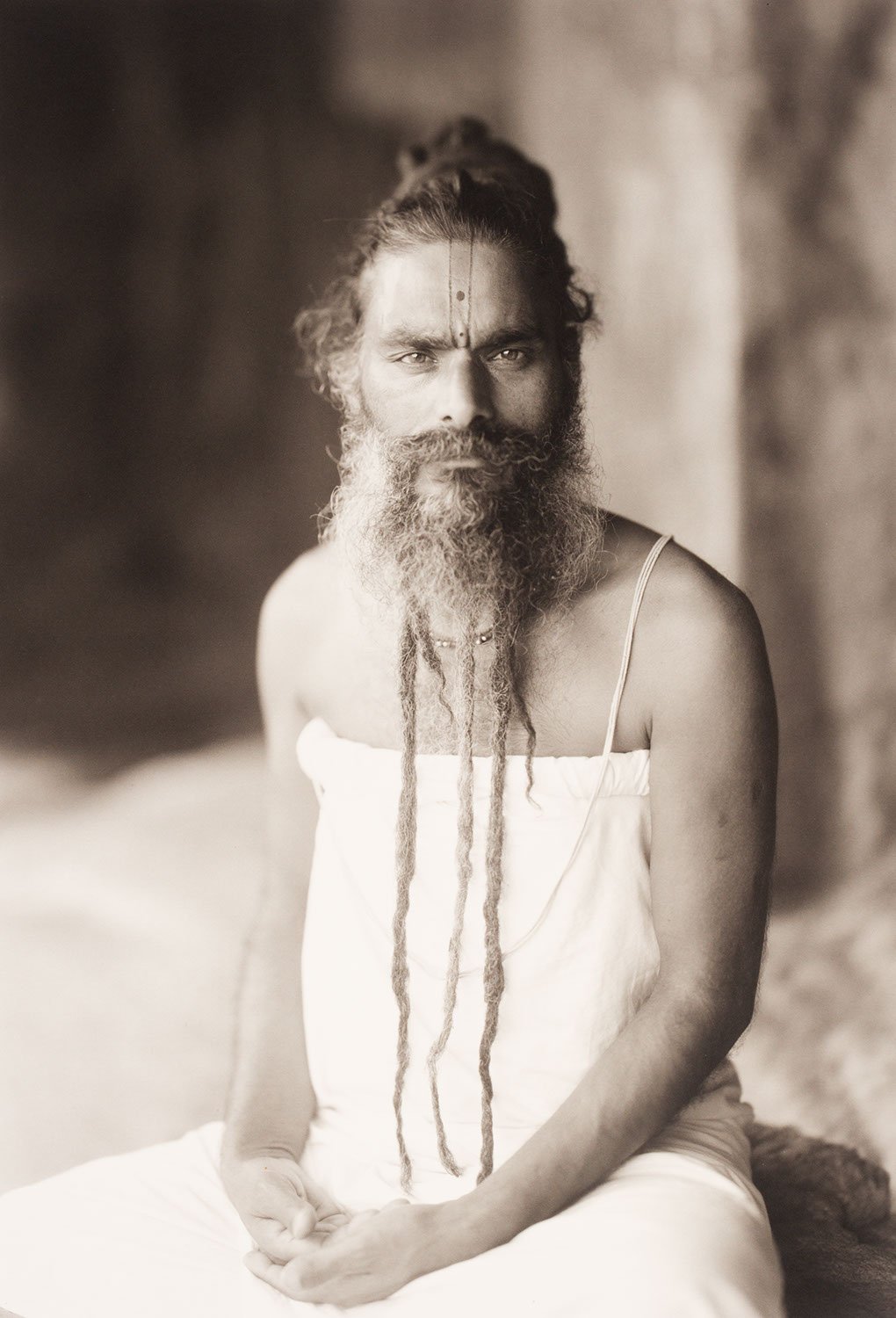

Kanchipuram # 647, Tamilnadu, India, 2012, Kenro Izu

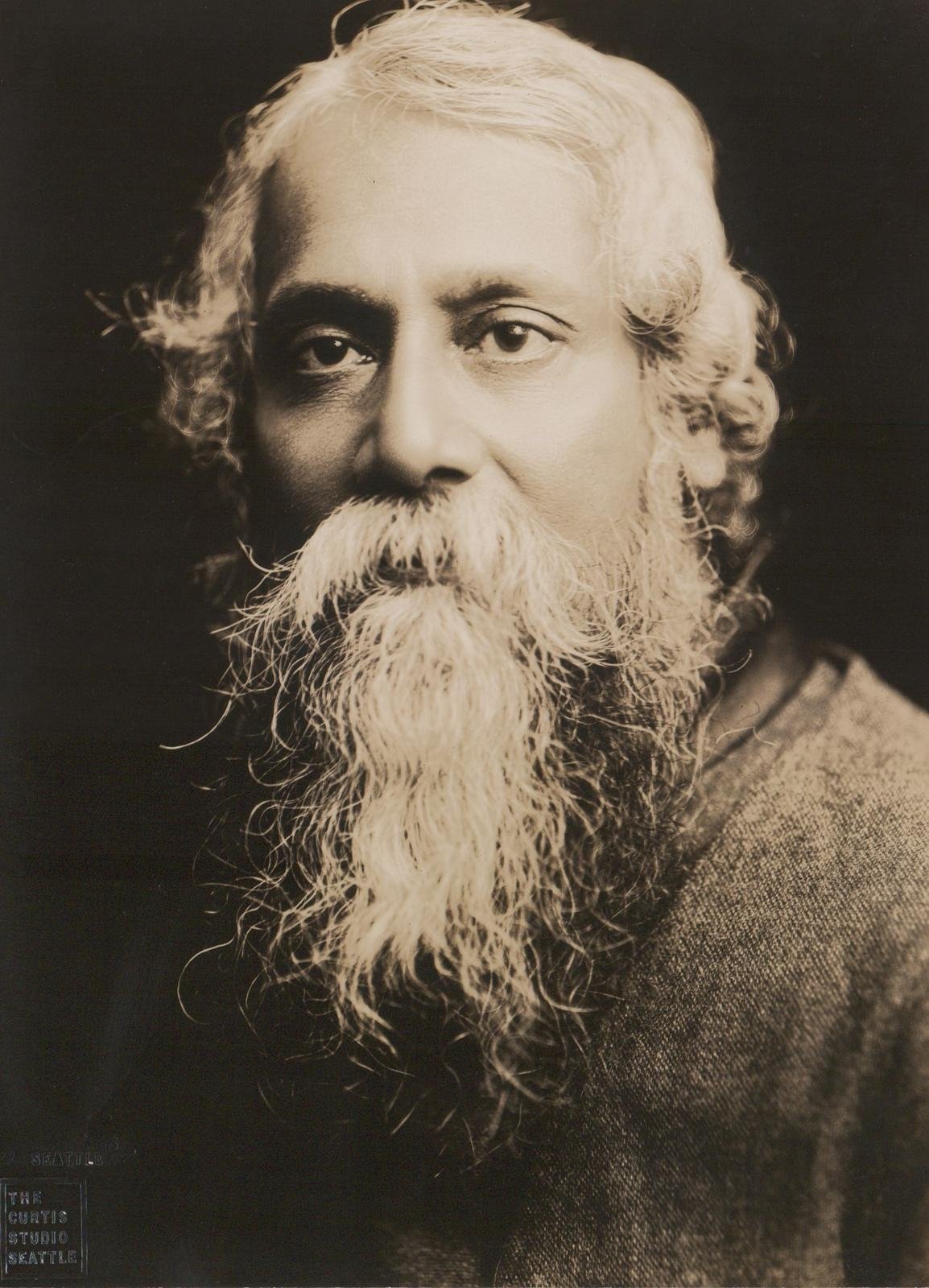

Like Kenro Izu a century later, Edward S. Curtis was careful in the arrangement of each of his portraits, even going to the extent of removing markers of modernity, like his subject’s watches from his photographs, to ensure the illusion of a timeless image never shattered.

Rabindranath Tagore, 1916. Edward S. Curtis

India - Where Prayer Echoes

India - Where Prayer Echoes is the title of a series of photographs by the Japanese photographer Kenro Izu.

I can’t figure out why this image is titled Erola #460. Where is Erola? Of course, it could just be a titling error; perhaps he meant Ellora, a famous rock-cut cave complex in Maharashtra.

But that is such a minor, insignificant detail.

I find myself both irresistibly drawn in, and also hesitant to write about this image. It is a beautifully made photograph. The man’s eyes are piercingly in focus and his slightly crinkled brow only enhances his handsome face. He is most likely a Hindu Brahmin priest. The incredibly shallow depth of field of the photograph draws my gaze into this man’s eyes and holds my attention as the background melts away behind him.

As a portrait, this photograph is brilliantly successful.

Despite its beauty, however, it remains an uncomfortable photograph to look at. A question swirls around in my head - does the artist owe their responsibility to beauty or to truth?

The depiction of India as an ancient, unchanging land suffused with spirituality is a very old tradition. Its roots can arguably be traced all the way to the early Buddhist pilgrims chronicling their travels through the Indian subcontinent in the 5th century CE. And one can easily imagine this image being recognisable to those early travellers. There is not a single peek of modernity in Kenro’s photographs from this series. That is a stylistic choice of course, but it is also revealing.

Although photography is a distinctly modern medium of representation, its use as a means to capture that which is ‘timeless’ – people, cultures, and ideas has been almost as widespread as its use as a tool to further the image of modernity.

These photographs remind me of the depiction of another culture deemed ‘ancient and unchanging’ – the photographs made of Native American people by the white American photographer Edward S. Curtis.

Chief Joseph, 1903. Edward S. Curtis, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Jean-Antony du Lac

Edward S. Curtis also photographed one of the most famous Indians of the early 20th century, the artist, poet and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore, and looking at this photograph again, I see the carefully constructed timelessness – here is the wise Indian Sage.

I return to Kenro Izu’s photograph of his own ‘wise Indian Sage’. The discomfort of a photograph that is almost too beautiful – a beauty that drapes liquidly over the violence of caste and religion; a Brahmin priest as the symbol of a spiritual India grates at me. The deep stillness of the image indicates an unshakable constancy that is

Erola #460, Maharashtra, India

2012

Kenro Izu