Or there you are, one of the fifteen-odd people who happened to be passing by that day, rooted to the spot, watching. Perhaps one of the children, watching another child running. Fearing it, and yet possibly knowing already, that this would never happen to you. There you are, in perpetuity. If you saw this in the museum, would you recognise yourself? Would you remember?

Photography has two significant gifts. One is its ability to record time passing, and the other is its ability to record time frozen. But this is not new gospel in any way. Most of us alive today have photographed, and have been the subjects of photography in innumerable instances throughout our lives, and we all know this; in an intuited, if not learned way. But this was not the case in 1977. To be photographed in 1977 in India, even in its capital city New Delhi, you had primarily one of three ways:

You had the money and the inclination to buy a camera and film, set it up appropriately and put yourself and (more often than not, your friends and family) in front of it. You purchased also a shutter release cable, and a tripod if you could manage it. Once the frame was in place, everyone was visible and in focus, the room stopped breathing, and you released the shutter. Then you found 35 other things to take pictures of (if you had a 35mm camera), and you finished the roll of film. After this, you made the time to go to a film processing lab, hand over your film and more money, wait a few days, and finally received your photograph, in print. You arranged it in an album and maybe decided to take more pictures since you put in so much time and money in the first place. (A hobby potentially emerged).

You went to a photo studio (often attached to film processing labs), and you got yourself photographed professionally. You handed over some money, waited a few days, and received a scant few prints of a moment of your life forever frozen (you were already a different person by the time you saw these pictures). Since you didn’t have too much money, and perhaps didn’t wish for your mundane life to be overly recorded, your photographed self existed as records of birthdays, graduation, a wedding, and so forth. A scant album, but one of seriousness and significance. Particular significance if your life was not considered to be of archival value by the world around you. (To record is to resist).

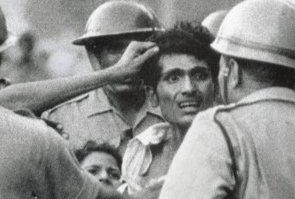

You had the misfortune to find yourself on a photojournalist’s path in one of the most terrifying moments of your life. There you are, frozen, forever, as your hair is being ripped out.

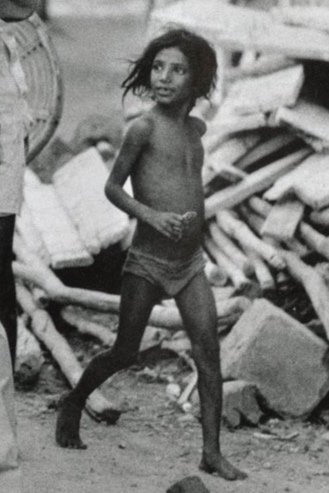

Or there you are, running, to protect yourself, a child, now almost sixty.

Here you are, just another day on the job. A mundane moment of your life you did not care to have a record of.

The caption of the photograph says that it was made during a protest.

January 30th 1977 saw India’s first large-scale protest since the lifting of the Emergency by India’s then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi. But there was no known violence that evening. So this image is likely not from that day.

A forgotten protest, one not recorded with the intensity of major news events in the country’s history. Too mundane to be in the official album.

A year before in 1976 however, there was a violent protest in New Delhi. Many people were killed, and their homes were demolished. The Turkman Gate demolition is considered to be the first time bulldozers were brought into the heart of New Delhi to raze homes that had been inhabited for generations by people deemed inconvenient; a sight that has since become familiar to us, mundane even.

People fighting for their right to exist, amidst the rubble.

Here you are, desperately trying to protect someone you love from the violence of the state. Your bangle-adorned hand entangled in the photograph with those of the men duty bound to hurt you. What did you feel when you noticed the photographer five feet away, aiming his camera at you?

During a Protest, Delhi

1977

Raghu Rai